Chris Tidy on understanding the risks around head injuries in construction.

We’ve all seen the headlines about head injuries in sports such as elite rugby, football, NFL and boxing. The injuries lead to potentially severe cases, long-term issues and degenerative brain conditions caused by multiple head impacts, known as sub-concussions.

Most of us face the risk of head injury at work, as well as in play. Some face this risk more than others, including those who work within the construction, industrial and utility sectors.

Safety helmets and hard hats have been protecting people in one form or another for thousands of years. From their humble beginnings as battle armour in 2500BC to today, where their use is much more widespread, they have stood the test of time. Despite having one of the highest wearer compliance rates of all PPE products and the widespread and mostly mandatory use of hard hats, construction and industrial workers are still at risk of severe head injuries, including concussions. They can suffer concussions from the impact force from a slip, trip or fall, as well as falling objects.

Whether the injury is from the ground after a slip, trip or fall, or if a falling object hits the head, it is likely to be an angled impact, which could introduce a rotational motion to the head. Conventional hard hats protect against injuries such as skull fractures, but are often not designed to address rotational motion.

Most valuable asset

Our most valuable asset to protect is our head because that is the bit that works everything else. If something happens to it, the implications are serious, including anything from brain injury to death.

Although we see high compliance and usage, employers and end-users often default to the lowest-cost solution when procuring safety helmets, as long as it meets standards. But standards are only the minimum level of protection. We need to understand more about the different levels of protection that hard hats can give the wearer. And we need a better understanding of the helmet technologies and the real risks that wearers of head protection face on a daily basis.

We can gain a further understanding of how injuries are caused and how we can prevent them through accident reporting and statistics. But this is only one part of the equation. As an industry, we must continue to analyse and question statistics to address the issues that significantly impact wearer safety.

To prevent head injuries on site, we must first understand the risk. This involves educating the supply chain and changing the whole industry perspective. There are a lot of accident records and statistics available online; however, interpreting these is key to understanding and evaluating the risk.

Exact injury information needed

We know that in 2018/19 in the UK, there were 16 fatal injuries involving being struck by a moving or flying/falling object. But we do not know which ones involved a head injury. There were 749 incidents in the UK in 2018/19 where a head injury or asphyxia caused a loss of consciousness. But how many were explicitly caused by a head injury? And we know that more head injuries occur from slips, trips and falls from the same level or one level above than being struck by an object, but the focus until recently has been on protecting against being struck by an object.

The reason for this is perhaps because the industry reports on accidents and not injuries, hence why the injury portion is inaccurate. It would be better if more emphasis were placed on the exact injury information, which was logged in detail. We could then understand the injuries more and help to mitigate them.

Better accident reporting

We must continue pushing for better, more detailed accident reporting and statistics to take the proper steps to protect people and ensure we focus on the areas that can have the most significant impact on wearer safety. For example, traumatic brain injury (TBI) and rotational injury. The most common type of TBI is a concussion, which accounts for up to 75% of all TBI cases.

These injuries are far more common than you think. 50% of TBIs go undiagnosed or detected, while 90% of diagnosed TBIs do not involve a loss of consciousness. Accident data and statistical analysis are likely to help us to achieve a higher level of protection for the wearer, but only if we push for better data quality and use it to inform future product development.

Protection from rotational brain injuries

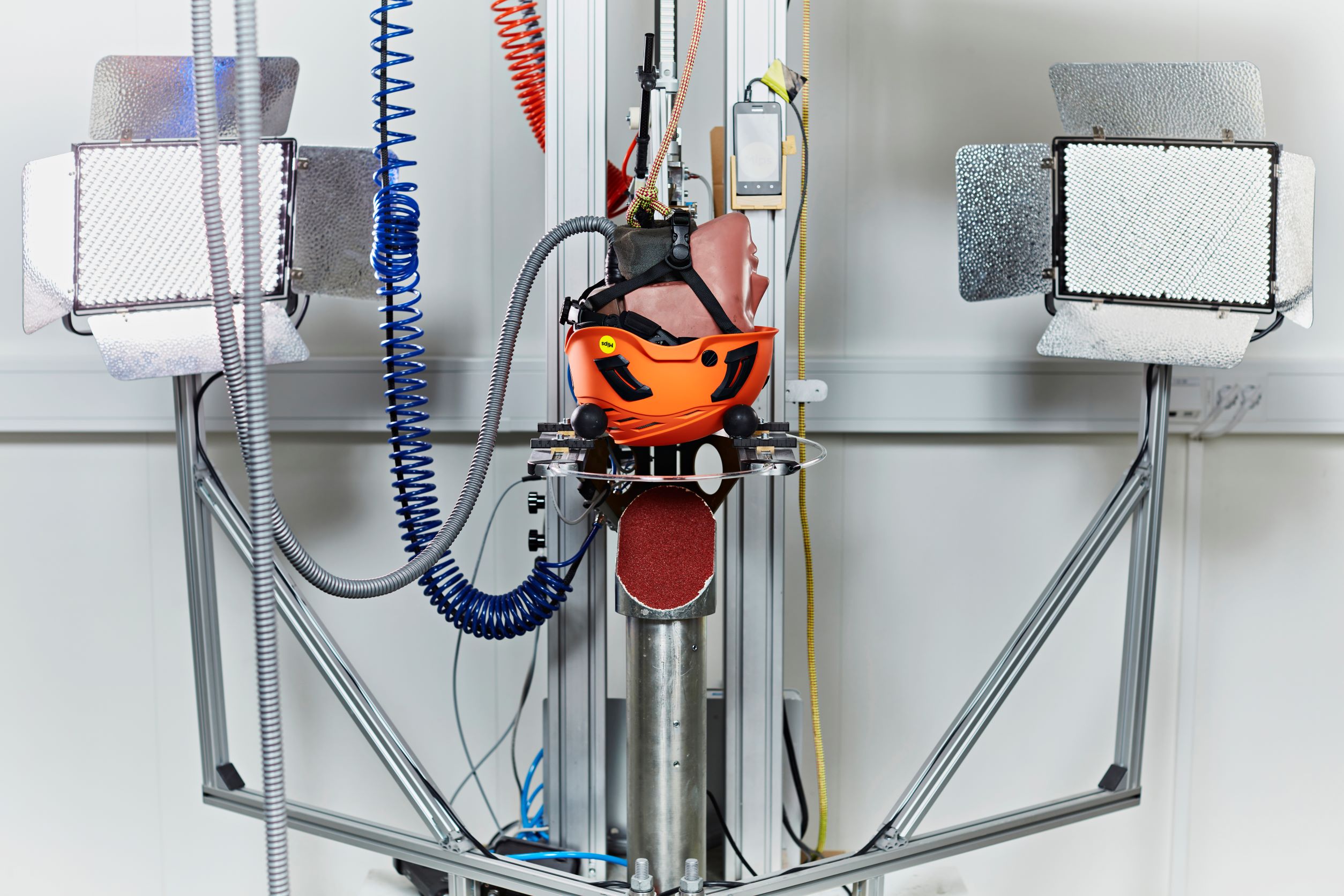

Many of us have seen EN397 safety helmet shock tests where a linear force is directed onto a safety helmet from height, and in most cases, the hard hat remains intact. This test is a sobering reminder of the importance of wearing head protection and demonstrates that these safety helmets are relatively good at absorbing linear impacts.

The problem is that most traumatic head injuries are not caused by a linear impact to the crown of the safety helmet. Research shows that you are more likely to acquire a long-term injury from a fall than from a falling object. Still, when falling objects cause injuries, they rarely fall straight down and cause a linear impact – for example, when a brick falls, it might hit the scaffolding or re-bound off some hoarding before striking the safety helmet with a non-linear impact.

A rotational brain injury results from a rapid change in the rotational velocity of the head. This rapid change can be caused by a direct hit to the safety helmet or the skull or by an indirect hit to the shoulder, leading to a rotational head motion. Injury statistics show it is most common to fall at an angle when you fall and hit your head, compared to a linear fall. Falling at an angle creates rotational motion, and science has shown that our brains are particularly susceptible to rotational forces. In an angled impact, these forces may transfer to your head.

Helmet technology

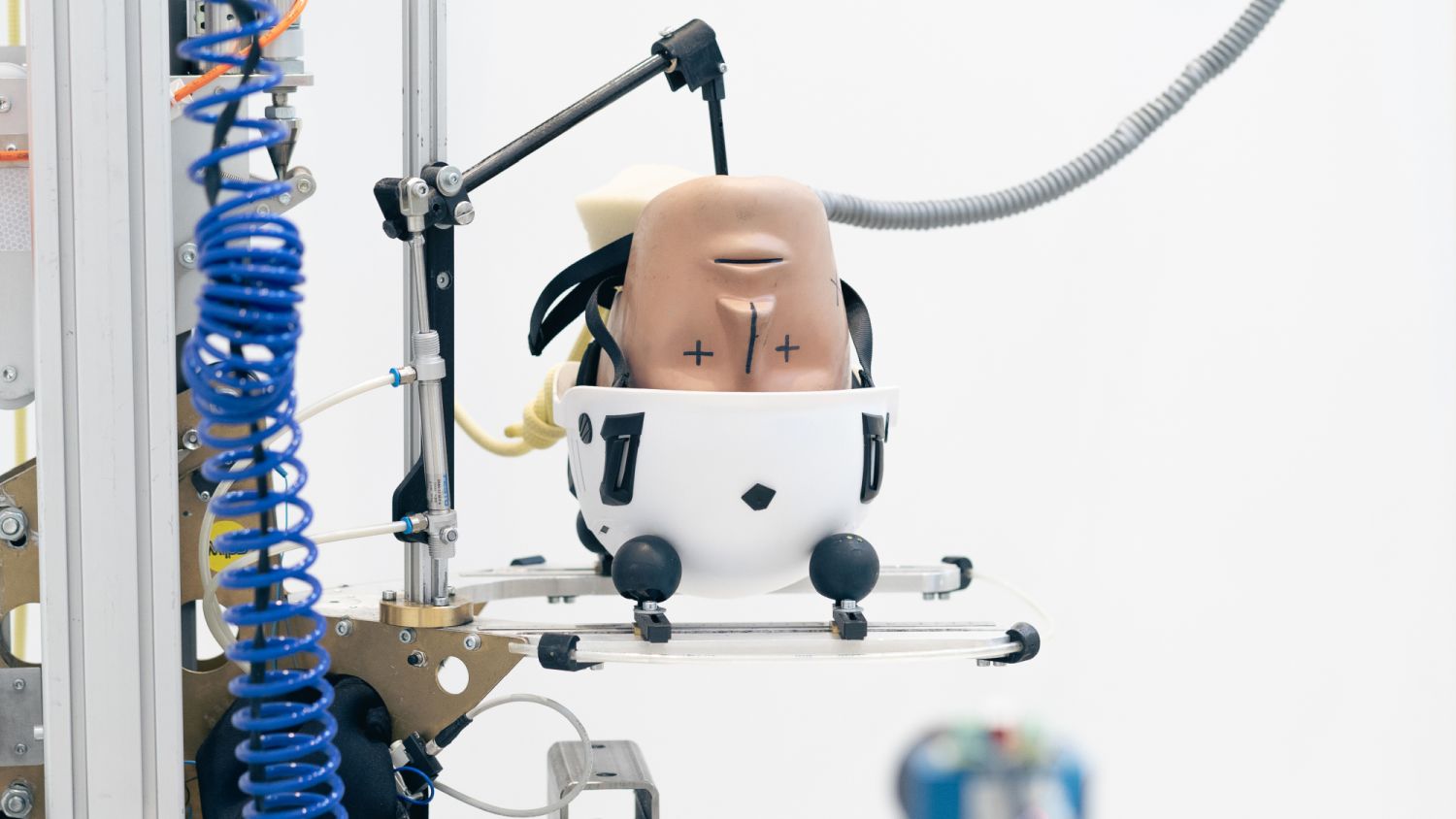

Some developments in safety helmet technology are designed to reduce the risk of traumatic brain injuries. The helmet technology company, Mips, is already well known in sports and motorcycle helmets and is popular among skiers and cyclists. It has partnered with leading PPE manufacturers globally to incorporate a patented low-friction layer into safety helmets.

The low-friction layer allows the head to move inside the helmet (10–15mm relative motion in all directions), which is designed to help redirect harmful rotational motion that would otherwise be transferred to the head. The intention is to improve head protection by reducing harmful rotational motion caused by an angled impact from a worker falling or being struck by a falling object.

At Mips, we work closely with safety professionals and industry institutions to encourage best practices around safety equipment and awareness of head injuries and educate on real-life impact scenarios, rotational injuries and how they occur. We will continue to challenge the status quo and push technical boundaries with the intention of improving head safety.

Chris Tidy is a product/training specialist at Mips and founder of Hard Hat Awareness Week.